In August 2023, Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) made a startling claim: the nation’s unemployment rate had plummeted to 4.1 percent. This figure, a stark departure from the 33.3 percent rate stagnant since 2021, sent ripples of scepticism across the populace.

As the people dwell in doubt, the data processing unit confirmed its latest report was not a reflection of reduction in unemployment but of a change in research methods, a shift to a revised methodology that aligned with the International Labour Organization’s guidelines. However, this new approach made a joke of the grim reality of the country’s unemployment and poverty, and could misinform the government of the true state of its citizens.

Nigeria, home to over 225 million people, boasts a labour force where 68 percent have completed secondary education, qualifying for civil service roles that pay a minimal ₦33,000 monthly. Yet, this wage barely sustains a middle-class family, especially against the backdrop of rampant inflation where every family spends over N48,000 a month on food alone. So what do we call an employment that barely feeds the family?

Under the NBS’s new system, ’employed’ individuals are anyone in the working-age population who engage in any activity to produce goods or provide services for pay or profit. In contrast, the ‘unemployed’ are those not employed, actively searching for work, and available—currently doing nothing for pay or profit. This approach differs markedly from the previous methodology. Before now, the ’employed’ included not only those working full-time but also individuals engaged in activities that produce goods or provide services for at least 20 hours. Conversely, the ‘unemployed’ category encompassed those who work less than 20 hours or did not work but are actively searching and available to work.

While this change might seem minor, the resulting statistics raise critical questions. The new method’s outcomes significantly differ from previous data, prompting a reexamination of how employment figures are calculated and what these numbers truly represent about Nigeria’s labour market.

There is a reason the previous statistician at the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics adopted the later version, and the obvious one is that the ILO’s method does not reflect the reality of the Nigerian labour market.

One of the concerns is whether to consider a person whose job cannot sufficiently feed his family ‘employed’.

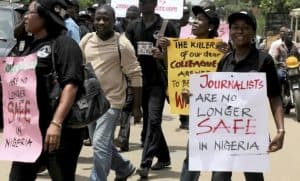

The widespread agreement is that recognising a problem is the first step towards solving it, as this acknowledgment paves the way for critical examination and resolution. This principle underlies the intense reaction to the National Bureau of Statistics’ (NBS) recent update, which came with an eagerness to position Nigeria on par with global economic giants.

In the United Kingdom, for instance, the unemployment rate recently rose to 4.3 percent in July 2023. This is a country where the average monthly earnings of employees were £2,111 as at October 2023, which equaled roughly $2,724.

According to Professor A S Abdullahi, the Dean of Postgraduate Studies and a professor of Development Economics at the Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, the NBS data is a political facade, unlikely to influence genuine economic planning. In his words, the data does not reflect the reality, “they [NBS] are only producing [such] data for the nationals, to give the impression that the government is doing well.”

This opinion echoes the national frustration: statistics failing to reflect the struggles of educated, yet unemployed or underpaid Nigerians.

The NBS’s report should be seen not just as data presented but also from the perspective of the implications such statistics have on shaping macroeconomic policies, potentially influencing Nigeria’s economic growth and development in the long term. Government uses these types of metrics to determine what to tax and who to tax, and the data processing unit might just be laying a foundation for the government to trap the poor struggling working class into taxation.

As we step into 2024, Nigerians hold onto a fragile optimism, hoping the next batch of NBS statistics will not be another distortion of their stark reality. The government’s reliance on such data could deepen poverty and devalue education, pushing the nation further into socio-economic despair.

The importance of data and statistics in formulating economic policies cannot be overstated. They inform the government in enacting laws and formulating regulations. Therefore, as the country transitioned to another year, the NBS better review its research methodology when producing its next report, the one that speaks to the reality of unemployment and the economic situation of all Nigerians.